Imagine a person, years dead. A dead poet. Physically gone, or so it seems. A plait of hair in an archive still shiny, still lustrous and alive, handwritten manuscripts with ink blotches and fingerprint smears, spilt coffee stains, traces of skin cells, tears, blood. Laundry lists, household chore rotas, menu plans, half sewn scarlet material lying in a sewing machine, cheque stubs, receipts, the blue eye of the turquoise swinging on its silver chain. Traces, residues. What constitutes a body of work asks Foucault? Is it everything that someone has ever written, uttered, deleted? Passages, drafts, plans? He asks, ‘How can someone define a work amid the millions of traces left by someone after his [sic] death?’ (104).[1] Things are somehow more solid than traces, more there and the temptation is to treat them as something more reliable because of this physical presence. Both in conversation and in her writing, Plath discussed just how this solidness seemed important:

I do not trust the spirit. It escapes like steam

In dreams, through mouth-hole or eye-hole. I can’t stop it.

One day it won’t come back. Things aren’t like that.

They stay, their little particular lusters

Warmed by much handling. They almost purr.

Last Words (172)[2]

There is an uncontrollability and unpredictability about something that ‘escapes like steam’ – it can’t be stopped. It is also impermanent and irretrievable (‘one day it won’t come back’). In direct contrast, Plath’s speaker states clearly how things are not like that. They are permanent, they stay, respond to handling, enjoy handling even, so that they almost purr. The comforting solidness of these warm things in their little lustres explains further why in conversation Plath would state ‘I love the thinginess of things’. Indeed, her archives confirm Plath’s claim that things last and are durable. Her childhood paper dolls and toys, intricate pastel drawings, illustrated letters, locks of baby hair.

It must be remembered though that the importance of the objects lie not only in their physicality but in their significance and use to the person who is no longer alive. So, the seemingly solid based reality of these things becomes instantly undermined if we consider our fascination with them not so much as how-they-are-now but how-they-were-then. The relics that we invest so much meaning and value in, may for example, have been irritating clutter to Sylvia Plath. Once we have written shopping lists or menu plans, do we ever revisit them as sites of great knowledge or are they usually thrown away and forgotten about? Moreover, if Plath herself did not invest value in these objects, why would we? How can an object be both significant and unimportant at the same time?

Karl Marx discusses how the ‘mystical character of the commodity does not arise from its use-value’ (10).[3] Rather Marx suggests that something a little inexplicable can occur to objects, something almost secretive. He cites the example of a piece of wood made into a table. Although the wood is altered to become a table, the table continues to be wood. But for Marx, as soon as this table emerges as a commodity, something else happens, ‘it transcends sensuousness’ (ibid) and a whole range of unthinkable transformations can occur to this piece of wood until it ‘evolves out of its wooden brain grotesque ideas far more wonderful than if it were to begin dancing of its own free will’ (ibid).

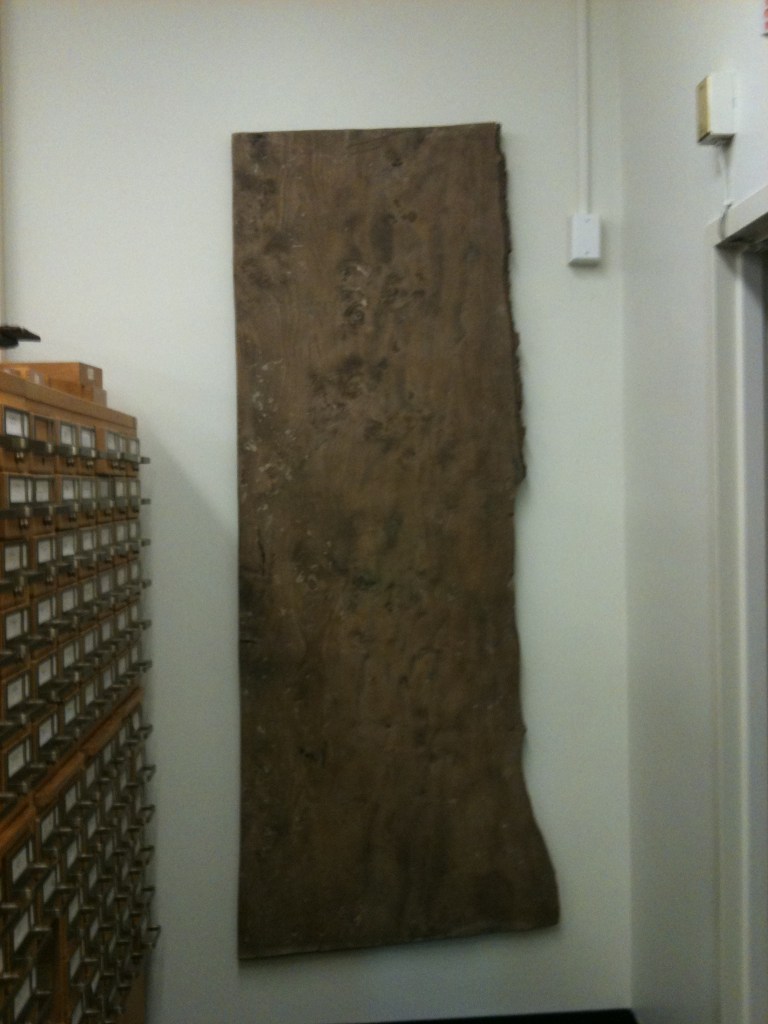

We see a fine correlation between Marx’s example of the table and one object stored in the Smith College Archives in Northampton, Massachusetts. For hanging there on the wall is the large six feet long elm plank that Sylvia Plath used as her writing desk. In itself, this is a piece of wood, wood made into a table and table that is still nevertheless wood. However, what occurred on this table (the writing of the Ariel poems), the person who used this table (Plath) lends a kind of mystical quality, a value that goes beyond economics. This elm plank is transformed in a way that we cannot quite define. Walter Benjamin (1973) describes the ‘aura’ of an original object and how this aura exists simply because the object is unique. The more an object is reproduced, the more precious the original becomes. Yet in the case of Plath’s desk, although it may be reproduced visually at least, it cannot be reproduced in any other way. There is only one desk upon which she wrote those Ariel poems, there is only this one desk that holds the ink stains and traces of that time. It is this uniqueness that makes it so special and perhaps it is Benjamin’s notion of the aura which affords it what Marx calls a ‘mystical quality’.

Perhaps it is because objects are curious things. Often inanimate and ordinary, they can be transformed into something imbued with power and meaning. This transformation that occurs seems to be a process brought about by a complex use of fantasy, social meaning, and the cultural biography of the object.

In the recent Sotheby’s auction of Plath possessions there was a range of items, such as a tarot card deck, two wedding rings, letters, recipe cards, and family photographs. Each had a unique monetary and emotional value placed upon them. Each had, what Benjamin would refer to, as an auratic presence. The pleasing mystery is how that auratic presence transfers itself into an inanimate object and becomes active. Whatever that process is, seems to me to be the real valuable transaction taking place here. Unique and secretive. You can almost hear the objects purr.

[An adaption from my book The Haunted Reader and Sylvia Plath (2017), Chapter 5 ‘Objects’]

[1] Foucault, Michel, 1984. ‘What is an Author?’ in Rabinow, Paul, (ed.), The Foucault Reader. New York: Pantheon Books.

[2] Plath, Sylvia, 1981. Collected Poems. London: Faber & Faber.

[3] Marx, Karl, 2000. ‘The Fetishism of the Commodity and its Secret.’ in The Consumer Society Reader. (ed.), Martyn J Lee,Oxford: Blackwells.